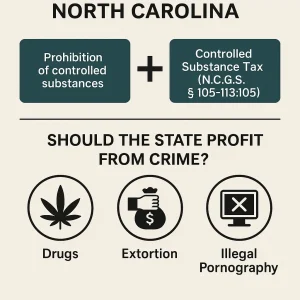

North Carolina law prohibits the possession, sale, and trafficking of controlled substances. Yet the same State that prosecutes those  offenses also taxes and therefore profits them. Is that right? Does that make sense? Should the government profit from crime? Is it OK to tax Drugs? Extortion? What about Illegal Pornography, Prostitution and Human Trafficking? Where do we, the governed, draw the line?

offenses also taxes and therefore profits them. Is that right? Does that make sense? Should the government profit from crime? Is it OK to tax Drugs? Extortion? What about Illegal Pornography, Prostitution and Human Trafficking? Where do we, the governed, draw the line?

The Controlled Substance Tax, codified at N.C.G.S. § 105-113.105, operates on the premise that illegal drugs have taxable value even though their sale and possession are criminal acts. The idea that “income is income” regardless of source smacks of Machiavelli and a willingness to bend basic moral imperatives. Beneath that procedural logic lies a troubling contradiction, if not outright hypocrisy.

Questions about punishment, profit, and fairness aren’t theoretical when you are the one standing before the court. North Carolina law distinguishes between fines, forfeiture, and taxation, but for clients facing criminal charges, those differences often feel academic. Bill Powers and the Powers Law Firm handle serious criminal matters in Mecklenburg, Union, Iredell, Gaston, Rowan, and Lincoln Counties, examining how the law operates in real courtrooms, not just in theory. Bill Powers is a widely regarded North Carolina criminal defense attorney, educator, and legal commentator with more than thirty-three years of courtroom and trial experience. He is recognized throughout the state for his work on impaired driving, criminal law, and legal education, and is a recipient of the North Carolina State Bar Distinguished Service Award. For select legal matters, Bill Powers consults on a statewide basis. To discuss your case in confidence, TEXT or call 704-342-4357.

Is it wrong when the State becomes a financial stakeholder in the very conduct it condemns? Some criminal charges in North Carolina already include mandatory fines that can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars and are paid directly to the State. For example, the Controlled Substance Tax may appear to be a technical revenue measure, yet its effect reaches far deeper. It touches the foundation of what separates criminal punishment from economic regulation and exposes how government can profit from the very system it is meant to restrain.

When the government taxes criminal conduct, it stops punishing and starts profiting. That is not justice. The State already imposes fines, court costs, and restitution, penalties meant to deter and punish. Adding a tax on top of that turns the process into revenue generation.

It reflects governmental overreach and feeds public cynicism because, following the logic (and mental gymnastics required to justify the conclusion) even for the most horrific offenses, the State could stand to gain financially. The message becomes clear. No matter the outcome, the House always wins. Imposing a fine as part of lawful punishment is one thing. Taxing a crime is something else entirely. It changes the purpose of punishment into profit and blurs the difference between a system of justice and a source of income.

The Origin of Taxing Crime Illegal Income

The concept that even illegal income is taxable did not originate in North Carolina. It traces back to the federal income tax decisions of the early twentieth century. In United States v. Sullivan (1927), the Supreme Court held that a bootlegger could not refuse to file a tax return on the ground that his earnings were illegal. Later, in James v. United States (1961), the Court reaffirmed that embezzled funds and other unlawful gains constitute taxable income.

The reasoning was practical, not moral.

Congress had defined gross income broadly, and the Internal Revenue Service sought to prevent criminals from shielding profits behind illegality.

The federal government’s motive was revenue protection, not ethical coherence – Bill Powers, NC Criminal Defense Lawyer

The result was a principle of tax law that disregards the source of income entirely. Once money is received and controlled, it becomes taxable.

Applied to ordinary commerce, that rule functions well enough. Applied to crime, it blurs the distinction between enforcement and participation.

When extended into state-level taxation schemes, it invites precisely the kind of constitutional issues (and moral ambiguity) in North Carolina’s Controlled Substance Tax.

The Structure of the Controlled Substance Tax and Taxing Crime in North Carolina

North Carolina adopted its Controlled Substance Tax in 1989.

The statute requires anyone in possession of certain quantities of drugs to pay a tax based on weight or dosage unit. Payment is theoretically anonymous, made by purchasing “drug tax stamps” from the Department of Revenue.

In reality, few, if any, offenders voluntarily pay. The tax is assessed after arrest or seizure, turning it into a post-arrest penalty rather than a legitimate revenue instrument.

The Department of Revenue can issue assessments, place liens on property, and seize assets to satisfy the tax. These powers mirror those used for ordinary tax collection but occur outside the criminal process. The amounts assessed can be substantial, and they compound fines already associated with criminal conviction.

From a policy standpoint, the statute operates as a hybrid between punishment and taxation. It does not deter conduct, because offenders rarely know it exists. It does not raise meaningful revenue independent of prosecution. What it does accomplish is to allow the State to recover money from those accused or convicted of drug crimes, sometimes even before conviction.

Historical Context of the Controlled Substance Tax in North Carolina

-

The tax was adopted by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1989 under S.L. 1989-772, establishing an excise tax on persons possessing controlled substances in violation of state law.

-

The timing corresponds with the height of the “War on Drugs” era, wherein federal and state policy emphasized criminal-enforcement responses to substance abuse, rather than public-health or regulatory models.

-

The tax reflects a policy logic. Illicit drugs have taxable value, so taxing them recovers revenue, even though the conduct is criminal. That mirrors older federal precedents such as the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act (1914) and the Marihuana Tax Act (1937) where tax stamps and excise-tax regimes were used to regulate or penalize illicit conduct.

Taxing Crime: Why It Matters

-

Symbol of the Drug-War Era

North Carolina’s drug tax is more than a fiscal measure. It stands as a vestige of a punitive philosophy toward drugs dominant in the 1980s and early 1990s—“Just Say No,” large-scale interdiction, severe penalties. In that climate, layering tax assessments on top of criminal sanctions fit a punitive framework more than a regulatory or rehabilitative one. -

Revenue and Punishment Converge

Because the State designed the tax to hit criminal actors for possession or distribution, its enactment marked a shift. North Carolina not only prosecutes crime, but financially capitalizes on it. This convergence of enforcement and finance raises questions of fairness, proportionality, and what the government’s role should be in profiting from crime. -

Administrative and Constitutional Frictions

Early versions of the tax were challenged on grounds such as double jeopardy and Fifth Amendment self-incrimination. While NC revised the statute to recast the tax as a civil assessment (a legal fiction) rather than purely punitive, such constitutional questions remain part of the tax’s history. - Policy-Mood Shift

In recent years, criticisms of the tax have grown alongside broader reconsideration of drug-war policies, criminal justice reform, and the role of enforcement in drug regulation. The historical momentum that produced the tax is now meeting structural and normative pushback.

Mandatory Minimums and Profit-Driven Justice in North Carolina

The Controlled Substance Tax did not appear in a vacuum. It arrived in 1989, at the height of the War on Drugs and near the peak of the “Just Say No” era. Legislatures across the country were embracing mandatory minimums, sentencing grids, and enhanced penalties that promised deterrence but often delivered disparity. North Carolina followed suit, adopting rigid sentencing laws and fixed penalties for trafficking under N.C.G.S. § 90-95(h).

Those statutes imposed minimum prison terms and steep mandatory fines based solely on drug weight. In serious cases, the fines reached hundreds of thousands of dollars, payable directly to the State upon conviction. The result was a system where punishment was both certain and profitable.

The Controlled Substance Tax extended that logic into the civil realm, allowing the State to collect money even before conviction and to pursue collection regardless of the criminal outcome.

Together, mandatory minimums and the Controlled Substance Tax formed two sides of the same policy coin.

One guaranteed incarceration and financial ruin for those convicted. The other ensured revenue flow even when cases faltered or were dismissed.

The combined effect blurred the line between justice and finance. The State became both prosecutor and creditor, pursuing punishment through prison and profit through taxation – Bill Powers, Criminal Defense Attorney

Federal courts eventually began to confront the harshness of mandatory sentencing.

The Supreme Court’s decisions in Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000), Booker v. United States (2005), and Kimbrough v. United States (2007) signaled a retreat from the mechanical application of mandatory penalties.

Those rulings restored some measure of discretion to judges and exposed the imbalance of a system that valued uniformity over fairness.

Yet state-level mandatory minimums in drug trafficking statutes remain deeply entrenched, and when coupled with financial assessments and taxes, they continue to produce outcomes where justice feels transactional.

The problem is not just excessive punishment.

It is the perception, and sometimes the reality, that the government has a financial stake in criminal enforcement.

When fines, forfeitures, and taxes converge, the purpose of punishment risks shifting from deterrence to collection.

That shift offends both constitutional principle and public trust.

Constitutional Collision of Taxing Crime: Lynn v. West

The constitutional infirmities of the Controlled Substance Tax eventually reached the courts.

In Lynn v. West, 134 F.3d 582 (4th Cir. 1998), the Fourth Circuit examined whether the tax, as then written, violated the Double Jeopardy Clause.

The Court held that the tax was punitive rather than civil in nature, given its high rates and the fact that it targeted conduct already punished criminally.

Imposing both the tax and a criminal sentence for the same act constituted double jeopardy.

In response, the General Assembly amended the statute, reducing rates and describing the tax as a civil assessment.

The changes were intended to align it with federal precedent distinguishing civil penalties from criminal punishment. Yet in practice, the functional character of the tax remained the same.

Assessments still occur after arrest, and failure to pay can lead to liens, garnishment, and forfeiture.

For the taxpayer, the difference between civil and criminal labels is semantic. The financial burden and stigma are identical.

The Ethical Problem of State Profit

Beyond the constitutional analysis lies an ethical question. Should the State profit from the very acts it defines as criminal?

The notion that government can collect revenue from wrongdoing contradicts the basic premise of criminal law, that certain conduct is so injurious to public order that it must not occur at all.

North Carolina does not sell licenses to commit burglary or impose filing fees for fraud or tax the distribution of prohibited pornographic content.

Yet it taxes possession of cocaine, heroin, or marijuana.

The result is a form of fiscal participation in crime. While the statutory language presents the tax purports to be neutral, its operation makes the State a beneficiary of illegal enterprise.

If one accepts the logic of taxing illegal income, the boundaries dissolve quickly.

Could North Carolina tax the proceeds of prostitution, human trafficking, or child exploitation?

The same rationale would apply.

Taxing crime exposes the moral absurdity of the system.

A government cannot simultaneously prohibit an act as inherently immoral and then collect a share of its profits without eroding its own legitimacy

Revenue Enforcement as a Vehicle for Search and Seizure outside the Fourth Amendment

The overlap between taxation and enforcement also invites abuse.

State v. Hickman (2025 NCCOA) illustrates how revenue powers can evolve into quasi-criminal authority.

In that case, Department of Revenue agents used a tax collection warrant to enter a private residence and conduct a search.

The Court of Appeals reversed the conviction, holding that a tax warrant authorizing levy and sale does not permit residential entry without a judicial search warrant.

The connection to the Controlled Substance Tax is not abstract.

Both regimes rely on administrative authority to pursue alleged criminal actors. Both risk conflating revenue collection with criminal investigation.

When fiscal enforcement becomes a back door into policing, the procedural safeguards that define criminal justice begin to erode – Bill Powers, Criminal Defense Attorney in Charlotte NC

The Practical Inefficiency of Punitive Taxation of Crime

Even if one sets aside moral and constitutional objections, the Controlled Substance Tax fails its pragmatic test.

It does not encourage voluntary compliance, and it rarely generates revenue except through forced collection.

Administrative resources are spent assessing and litigating taxes that are rarely paid voluntarily. The process functions more as a secondary punishment than a tax policy.

That inefficiency matters because it undermines the stated justification of revenue neutrality.

Policy Alternatives to Taxing Crime

North Carolina could correct course without weakening its stance on drug enforcement. Several approaches merit discussion:

-

Repeal or Reframe. The simplest solution is to repeal the Controlled Substance Tax. If the goal is deterrence or restitution, those ends can be achieved through sentencing and forfeiture statutes that operate within the criminal process.

-

Tie Assessment to Conviction. If the tax is retained, it should attach only after a judicial finding of guilt. That safeguard would prevent double jeopardy and align assessment with due process and the rule of law.

-

Dedicate Revenue to Treatment. Any funds collected should be earmarked for rehabilitation, education, or prevention, not deposited into general revenue. Doing so would shift the measure from profit to remediation.

A Return to Constitutional Coherence

The exclusionary rule teaches that government should not benefit from its own unlawful conduct.

The same logic applies here. The State should not benefit financially from conduct it has declared unlawful.

The Controlled Substance Tax stands as a relic of administrative convenience rather than constitutional principle. It survives because it is easier to collect than to justify.

Reconsidering the statute does not signal leniency toward drug offenses.

Punishment belongs to the judicial branch, not the tax collector. The moral authority of the State depends on the integrity of that division.

In light of Hickman and similar cases, North Carolina would do well to reexamine whether fiscal mechanisms that shadow criminal law serve justice or merely revenue.

Profit, Punishment, and the Rule of Law

Tax law and criminal law serve different purposes. One sustains government, the other restrains it. When the two converge, the result is moral opacity, if not downright hypocrisy. The Controlled Substance Tax embodies a Machiavellian approach to addressing crime. It transforms illegality into taxable value and turns punishment into profit. It makes the state a partner in crime, profiting from something that no one, particularly the government, should profit.

North Carolina’s decision to tax crime grew out of Prohibition-era enforcement and flourished during the War on Drugs, when punishment became policy and revenue followed punishment. What began as deterrence soon became profit. Fines, forfeitures, and taxes multiplied until the system learned to collect before it convicted.

The problem is not only constitutional, it is philosophical. A government that profits from the conduct it condemns ceases to act solely in the public interest. The Controlled Substance Tax blurs the boundaries that separate punishment from participation and justice from commerce. It reflects the excesses of the 1980s, when moral purpose yielded to the fiscal opportunism of bureaucracy.

Punishment should belong to the courts, not the Department of Revenue. Justice cannot be a balance sheet entry.

If you are facing a complex criminal charge, informed representation matters. Bill Powers, is a widely regarded North Carolina criminal defense attorney, educator, and legal commentator. He brings decades of courtroom experience to questions that define the limits of governmental power. The Powers Law Firm in Charlotte handles serious felony and constitutional matters in Mecklenburg, Union, Iredell, Gaston, Rowan, and Lincoln Counties, and for select issues, Bill Powers also consults on a statewide basis. To discuss your case in confidence, TEXT or call 704-342-4357.

Carolina Criminal Defense & DUI Lawyer Updates

Carolina Criminal Defense & DUI Lawyer Updates